I was looking for a job late last year when I saw a tweet about a place called Igalia. The more I learned about them, the more interested I became, and before long I applied to join their Web Platform team. I didn’t have enough experience for a permanent position, but they did offer me a place in their Coding Experience program, which as far as I can tell is basically an internship, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Here’s an overview of what I did and what I learned.

Contents

Why Igalia?

There’s a wide range of work I can do as a computer programmer, but the vast majority of it seems to be in closed-source web applications, as an employee with a limited voice in the decisions that affect my work.

At the time, all of my work since I graduated had been exactly that, or in builds and releases for said applications. That was interesting enough for a while, but I wanted to make a bigger impact, work on something I actually cared about of my own volition, and ideally move towards getting paid to do systems programming.

Igalia appeals to me, with their focus on open-source projects, systems programming, and standards work. Even better, as a field, the web platform has been my one true love, and building things on it is how I got into programming over 15 years ago. But what cements their place as my “dream job” is how they work: as a distributed worker’s cooperative.

What I mean by “distributed” is that members can work from anywhere in the world, paid in a way that fairly adjusts for location, and in whatever setting they thrive in (such as home). This alone was huge, as someone who can’t sustainably work in an office five days a week, had to move 4000 km away from home to do so, and had just left an employer that was actively hostile to remote work.

Andy Wingo (author of that tweet) offers some insight into the “worker’s cooperative” part in these three posts. Igalia’s rough goal here, as far as I can tell, is that everyone gets a voice in deciding what the collective works on and how (to the extent that those decisions affect them), equal ownership of the business, and equivalent pay modulo effort and cost of living. This appeals to me as an anarchist, but also as a worker that has often been on the receiving end of unethical work, poor working conditions, and lack of autonomy.

ſtylesheet

One goal of my internship was to help the Web Platform team with their MathML work, but I was also there to familiarise myself with working on the web platform, and my first task was purely for the latter.

Many parts of the web platform have case-insensitive keywords that control an API or language feature, like link@rel (the <link rel="..."> attribute), but thanks to Unicode, there’s more than one level of case-insensitivity.

Unicode case-insensitivity won’t break backwards compatibility of web content over time, but to improve interoperability and simplify implementations, things like the HTML spec tend to explicitly call for ASCII case-insensitivity, at least for keywords that are nominally ASCII.

That makes Blink’s widespread use of Unicode case-insensitivity in these situations a bug, and my job was to fix that bug, which sounds simple enough, until you realise that doing so is technically a breaking change. You see, there are already a couple of non-ASCII characters that can introduce esoteric ways to write many of those keywords.

More importantly, the web platform is almost1 unique in that breaking existing content is, in general, not allowed.

But this time a breaking change was unavoidable, like any time where an implementation is fixed to align with the standard, or some behaviour is standardised after incompatible implementations appear.

There might be content out there that relies on something like <link rel="ſtylesheet"> because it worked on Chromium.

There are a few ways to minimise the impact of these breaking changes, like adding analytics to browsers to count how many pages would be affected, or searching archives of web content, but in this case we decided the risk was low enough that I could simply fix the bug and write some tests.

- Chrome Platform Status entry

- intent to remove

- blink-dev thread

- analysis of deprecated call sites

- issue 627682: tracking bug for deprecated string operations

- issue 1060477: HTMLElement::ApplyAlignmentAttributeToStyle

- issue 1060495: HiddenInputType::AppendToFormData

- issue 1060499: <param name=”src” value=”…”> + <object data=”…”>

- CL 1997014: Element#insertAdjacentElement + Element#insertAdjacentText

- CL 2015875: DeprecatedEqual: safe subset part 1/2 (NFC)

- CL 2032654: DeprecatedEqual: safe subset part 2/2 (NFC)

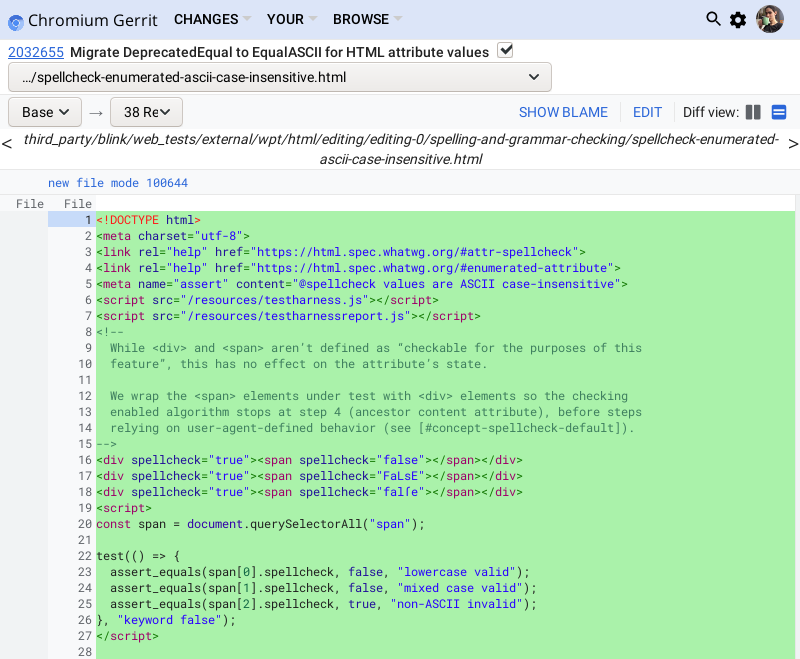

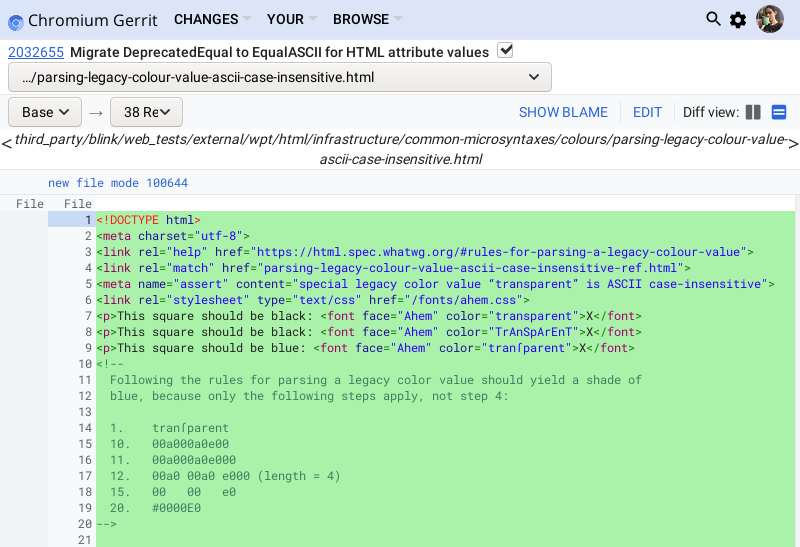

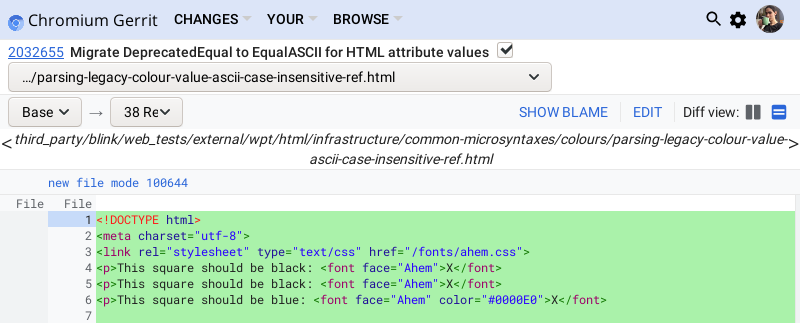

- CL 2032655: DeprecatedEqual: HTML attribute values (including WPT)

- CL 2106983: DeprecatedEqual: @import + @charset

- CL 2108441: DeprecatedEqual: all other ASCII literals

- CL 2113394: DeprecatedEqual: all other ASCII constants

- CL 2114510: DeprecatedLower: where only compared with ASCII

- CL 2121937: simplify MapDataParamToSrc (NFC)

Fixing the bug

It’s hard to get a usable LSP setup going for a project as big as a browser. I switched between ccls and clangd a bunch of times, but I never quite got either working too well. My main machine is also getting pretty long in the tooth, which made indexing take forever and updating my branches expensive.

I considered writing an LSP client that would allow me to kick off an index on one of Igalia’s 128-thread build boxes without an editor, but I eventually settled on using Chromium Code Search to jump around and investigate things. Firefox similarly has Searchfox2, but WebKit doesn’t yet have a public counterpart3.

I was looking for callers of three deprecated functions, but not all of them were relevant to the bug, and not all of those needed tests, and so on.

To help me analyse and categorise all of the potential call sites, I wrote some pretty intricate regular expressions for Sublime Text 2.

This one finds all callers of DeprecatedEqualIgnoringCase, with two arguments, where one of them is an ASCII literal that wouldn’t need new tests (skSK):

(?x-i)

(?<escape>\\['"?\\abfnrtv]){0}

(?<literal>"(?:(?=[ -~])[^"skSK]|(?&escape))*"){0}

(?<any>(?:[^(),]|(\((?:[^()]*|(?-1))\)))*+){0}

DeprecatedEqualIgnoringCase

(\s*\(\s*+(?:

(?&literal)\s*,\s*+(?&any)

|(?&any)\s*,\s*+(?&literal)

)\s*\))

After my first patch, which I wrote by hand, I also used those to do the actual replacing, maintaining a huge analysis of all the cases that remained after my second patch.

Writing some tests

Each of the major engines has its own web content tests, and automated tests are strongly preferred over manual tests if at all possible. All of the tests I wrote were automated, and most were Web Platform Tests, which are especially cool because they’re a shared suite of web content tests that can be run on any browser. Chromium and Firefox even automatically upstream changes to their vendored WPT trees!

Many of my tests were for values of HTML attributes whose invalid value default was a different state to the keyword’s state. In these cases, I didn’t even need to assert anything about the attribute’s actual behaviour! All I had to do was write a tag, read the attribute in JavaScript, and check if the value we get back corresponds to the intended feature (bad) or the invalid value default (good).

Some legacy HTML attributes are now specified in terms of CSS “presentational hints”, so I checked the results of getComputedStyle for those, but the coolest tests I learned to write were reftests. Very few web platform features guarantee that every user agent on every platform will render them identically down to the pixel, and over time, unrelated platform changes can affect a test’s expected rendering. Both of these things are ok, but they make it impractical for tests to compare web content against screenshots. Reftests consist of a test page that uses the feature being tested, and a reference page that should look the same without using the feature. The reference page is like a screenshot, but it’s subject to all of the same variables as the test page, such as font rendering.

Ever heard of the Acid Tests? Acid2 is more or less a reftest, because it has a reference page that only uses a screenshot for the platform-independent parts. Acid1 uses a screenshot of the whole test, hence “except font rasterization and form widgets”.

I had a lot of fun writing my two form-related tests, because I actually had to submit forms to observe those features’ behaviour. WPT has server-side testing infrastructure that can help with this, and for such tests, I would need to spin up the provided web server or run the finished product with wpt.live4.

In both cases, I avoided the need for that with a <form method="GET"> that targets an iframe, plus a helper page that sends its query string back to the test page.

MathML tasks

MathML was meant to be the native language for mathematics on the web, and that’s still true today, but two decades later, browser support still has a long way to go. There are several reasons for this, notably including the largely volunteer-driven development of MathML and its implementations, but over the last few years, Igalia has helped change that on three fronts: writing a Chromium implementation, improving the Firefox and WebKit implementations, and improving the specs themselves.

MathML 3 was made a Recommendation in 2014, and like any spec, it has shortcomings that only subsequent experience could identify. Proposals by the MathML Refresh CG like MathML Core are trying to address them in a bunch of ways, like simplifying the spec, setting clearer expectations around rendering, and redefining features in terms of better-supported CSS constructs. My remaining tasks touched on some of these.

mo@maxsize

Moving onto WebKit, my next task was to remove some dead code. Past versions of MathML specify a very complex <mstyle> with its own inheritance system that’s incompatible with CSS, as well as several attributes that were rarely if ever used by authors, both of which are a burden on implementors.

One of those attributes was mstyle@maxsize, which would serve as the default mo@maxsize instead of infinity. With the former removed from the spec, there was no longer a need for an explicit infinity value, so I removed the code for that.

It turns out WebKit never got around to implementing mstyle@maxsize anyway, so there was no functional change.

- mathml-refresh/mathml#1: simplify the mstyle element

- mathml-refresh/mathml#107: remove explicit mo@maxsize = infinity

- r259785: remove mo@maxsize value “infinity” (NFC) (bug 202720)

STIXGeneral

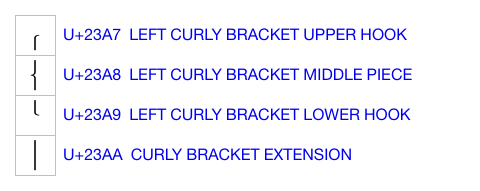

There’s a lot of MathML content that gets rendered like any other text, but stretchy and large operators are a bit more involved than just drawing a single glyph at a single size. A well-known example of a stretchy operator is square root notation, which consists of a radical (the squiggly part) and a vinculum (the overline part) that stretches to cover the expression being rooted.

Traditionally this was achieved by knowing where the glyphs for the separate parts lived in each font, so we could stretch and draw them independently. Unicode assignments for stretchy operator parts helped, but that wasn’t enough to yield ideal rendering, because many fonts use Private Use Area characters for some operators, and ordinary fonts don’t give applications the necessary tools to control mathematical layout precisely.

OpenType MATH tables eventually solved this problem, but that meant Firefox essentially had three code paths: one for OpenType MATH fonts, one with font-specific operator data, and one generic Unicode path for all other fonts. That second one adds a lot of complexity, and there was only one font left with its own operator data: STIXGeneral.

The goal was ultimately to remove that code path, dropping support for the font. That sounded easy enough until we realised that STIXGeneral remains preinstalled on macOS, as the only stock mathematics font, to this day.

My task here was to add a feature flag that disables the code path on nightly builds, and gather data around how many pages would be affected.

The patch was straightforward, with one change to allow Document::WarnOnceAbout to work with parameterised l10n messages, and I wrote a cute little data URL test page for the warning messages.

data:text/html;base64,PCFkb2N0eXBlIGh0bWw+CjxtZXRhIGNoYXJzZXQ9InV0Zi04Ij4KPHN0eWxlPgogIG1hdGg6Zmlyc3Qtb2YtdHlwZSB7CiAgICBmb250LWZhbWlseTogTGF0aW4gTW9kZXJuIE1hdGg7CiAgfQogIG1hdGggewogICAgZm9udC1mYW1pbHk6IFNUSVhHZW5lcmFsLCBMYXRpbiBNb2Rlcm4gTWF0aDsKICB9Cjwvc3R5bGU+CjxtYXRoIGRpc3BsYXk9ImJsb2NrIiBtYXRoc2l6ZT0iN2VtIj4KICA8bW8+4oiRPC9tbz48bW8gZGlzcGxheXN0eWxlPSJmYWxzZSI+4oiRPC9tbz4KPC9tYXRoPgo8YnV0dG9uIHR5cGU9ImJ1dHRvbiI+U1RJWEdlbmVyYWw8L2J1dHRvbj4KPHNjcmlwdD4KICBkb2N1bWVudC5xdWVyeVNlbGVjdG9yKCJidXR0b24iKS5hZGRFdmVudExpc3RlbmVyKCJjbGljayIsICh7IHRhcmdldCB9KSA9PiB7CiAgICBjb25zdCBzb3VyY2UgPSBkb2N1bWVudC5xdWVyeVNlbGVjdG9yKCJtYXRoIik7CiAgICB0YXJnZXQuYWZ0ZXIoc291cmNlLmNsb25lTm9kZSh0cnVlKSk7CiAgfSk7Cjwvc2NyaXB0Pgo=Turning the feature flag on broke a test though, and I couldn’t for the life of me reproduce it locally.

Fred and I tried every possible strategy we could imagine short of interactively debugging CI, on and off for six weeks, but it looked like the flaky behaviour involved some sort of race against @font-face loading.

Eventually we gave up and disabled the feature flag just for that test, and I landed my patch.

- mozilla.dev.tech.mathml: original context

- mozilla.dev.platform: intent to deprecate

- Firefox Site Compatibility note

- bug 1648335: STIXGeneral pref gate breaks semantics-1.xhtml

- D73833: STIXGeneral use counter and deprecation warning (bug 1630935)

- D77067: refactor FontFamilyName + FontFamilyList + nsMathMLChar (NFC)

padding + border + margin

Another way to improve the relationship between MathML and CSS has been defining how existing CSS constructs from the HTML world, including the box model properties, apply to MathML content. In this case, the consensus was that these properties would “inflate” the content box as necessary, making the element occupy more space.

Existing implementations in WebKit and Firefox didn’t really handle them at all because it wasn’t in the spec, so the last task I had time for was to change that.

A modern browser starts by parsing documents into an element tree, which is also exposed to authors as the DOM, but when it comes to rendering, that tree is converted to a layout tree, which represents the boxes to be drawn in a hierarchy of position/size influence. The layout tree consists of layout nodes (Chromium), renderer nodes (WebKit), or frame nodes (Firefox), but these all refer to the same concept.

I started with Firefox and <mspace> because that was the only element that could not contain children.

<mspace> represents, well, a space.

It has attributes for width, height (height above the baseline), and depth (height below the baseline), each of which can be negative to bring surrounding elements closer together.

I found the element’s frame node and noticed this method:

void nsMathMLmspaceFrame::Reflow(nsPresContext* aPresContext,

ReflowOutput& aDesiredSize,

const ReflowInput& aReflowInput,

nsReflowStatus& aStatus) {

// [...]

mBoundingMetrics = nsBoundingMetrics();

mBoundingMetrics.width = mWidth;

mBoundingMetrics.ascent = mHeight;

mBoundingMetrics.descent = mDepth;

mBoundingMetrics.leftBearing = 0;

mBoundingMetrics.rightBearing = mBoundingMetrics.width;

aDesiredSize.SetBlockStartAscent(mHeight);

aDesiredSize.Width() = std::max(0, mBoundingMetrics.width);

aDesiredSize.Height() = aDesiredSize.BlockStartAscent() + mDepth;

// [...]

}

Reflow is the process of traversing the layout tree and figuring out the positions and sizes of all of its nodes, and in Firefox that involves a depth-first tree of nsIFrame::Reflow calls, starting from the initial containing block.

An <mspace> frame never has children, so our reflow logic was more or less to take the three attributes, then return a ReflowOutput that tells the parent we need that much space.

To handle padding and border, we add that to our desired size.

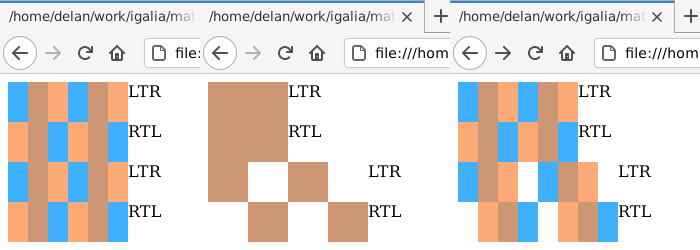

“Physical” here means the nsMargin in terms of absolute directions like left and right, as opposed to the LogicalMargin in terms of flow-relative directions, which are aware of direction (LTR + RTL) and writing-mode (horizontal + vertical + sideways).

We want to use LogicalMargin in most situations, but MathML Core is currently strictly horizontal-tb and sums of left and right are inherently direction-safe, so nsMargin was the way to go here.

auto borderPadding = aReflowInput.ComputedPhysicalBorderPadding();

aDesiredSize.Width() = std::max(0, mBoundingMetrics.width) + borderPadding.LeftRight();

aDesiredSize.Height() = aDesiredSize.BlockStartAscent() + mDepth + borderPadding.TopBottom();

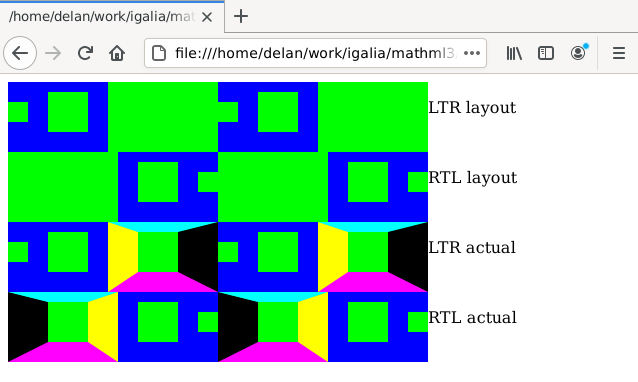

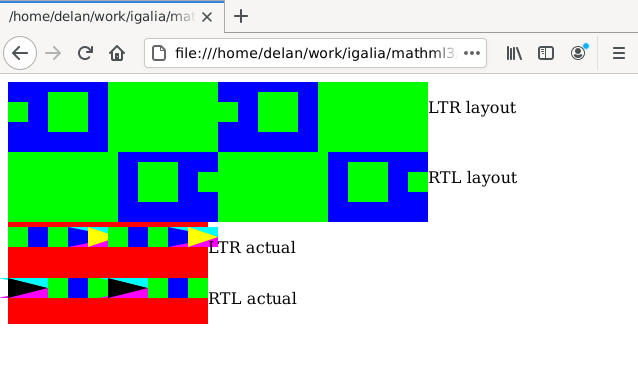

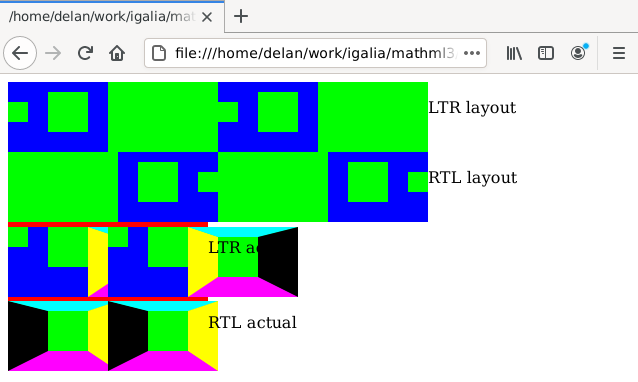

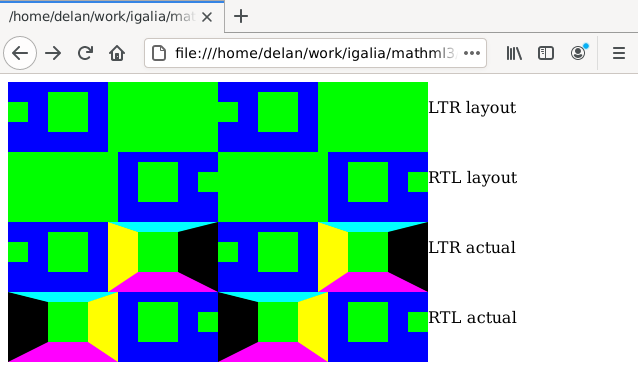

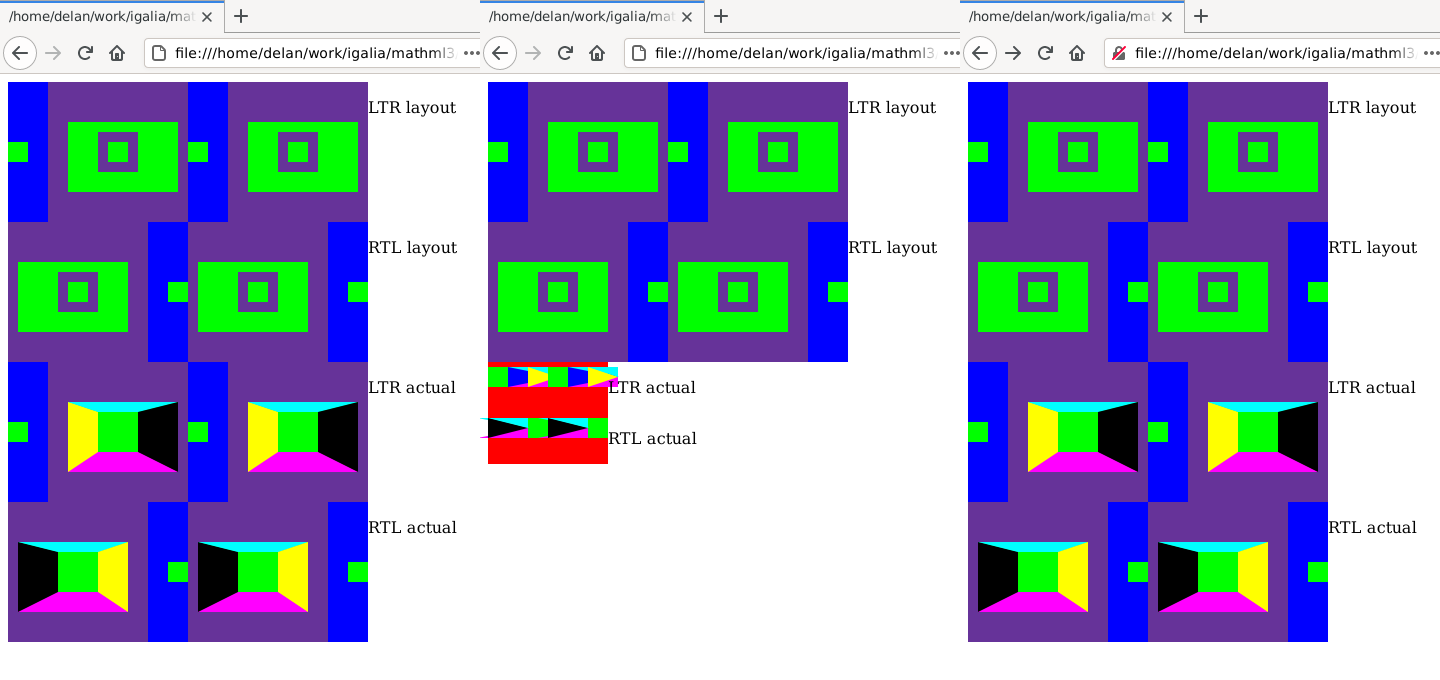

That was enough to pass the <mspace> cases in the Web Platform Tests, but the test page I had put together to play around with my patch yielded both good news and bad news. Let’s look at the reference, which uses <div> elements and flexbox rather than MathML.

The good news was that Firefox already drew borders, or at least border colours, even though the layout of them was all wrong.

The bad news was that while my patch made each element look Bigger Than Before, the baselines were misaligned. More importantly, the <mspace> elements and even the whole <math> elements still overlapped each other… almost as if… their parents were unaware of how much space they needed when positioning them!

I fixed the first two problems by adding the padding and border to the nsBoundingMetrics as well, because that controls the sizes and positions of MathML content.

That left the overlapping of the <math> elements, because while they contain MathML content, they themselves are HTML content as far as their ancestors are concerned.

auto borderPadding = aReflowInput.ComputedPhysicalBorderPadding();

mBoundingMetrics.width = mWidth + borderPadding.LeftRight();

mBoundingMetrics.ascent = mHeight + borderPadding.Side(eSideTop);

mBoundingMetrics.descent = mDepth + borderPadding.Side(eSideBottom);

It turns out that in Firefox, MathML frames also need to report their width to their parent via nsMathMLContainerFrame::MeasureForWidth.

With the <mspace> counterpart updated, plus the WPT expectations files updated to mark the <mspace> test cases as passing, my patch was ready to land.

/* virtual */

nsresult nsMathMLmspaceFrame::MeasureForWidth(DrawTarget* aDrawTarget,

ReflowOutput& aDesiredSize) {

// [...]

auto offsets = IntrinsicISizeOffsets();

mBoundingMetrics.width = mWidth + offsets.padding + offsets.border;

// [...]

}

I also put together a test page (reference) for the interaction between negative mspace@width and padding, which more or less rendered as expected, but it potentially revealed a bug in the layout of <math> elements that are flex items.

My guess is that flex items use a code path that clamps negative sizes to zero at some point, like we have to do in ReflowOutput, resulting in excess space for the item.

Margins were trickier to implement because, with Firefox and MathML content at least, the positions of elements are the parent’s responsibility to calculate.

I spent a very long time reading nsMathMLContainerFrame, which is the base implementation for most MathML parents, and eventually figured out where and how to handle margins.

With a patch that updates RowChildFrameIterator and Place, and yet another test page (reference) that passed with my patch, we were close to having a template for the remaining MathML elements!

You can see my approach over at D87594, but the patch needed reworking and I ran out of time before I could land it.

- mathml-refresh/mathml#14: padding + border + margin

- bug 1658135: <math> layout changes depending on presence of <mrow>

- D86471: implement padding/border layout for <mspace> (bug 1658121)

- D87594: implement margin for nsMathMLContainerFrame children (bug 1663867)

- reftest for padding + border on <mspace> (reference page)

- reftest for padding with negative mspace@width (reference page)

- reftest for margin on <mspace> (reference page)

Acknowledgements

This internship was incredibly valuable. While I was only able to finish the first trimester for mental health reasons, over the last nine months I’ve learned C++, learned how the web platform and browser engines work, gained ample experience reading specs, worked with countless people in the open-source community, and contributed to three major engines plus the Web Platform Tests.

Were I able to continue, I would also look forward to (more) experience contributing to specs, and probably helping Igalia with their MathML in Chromium project. In any case, my time with the collective has only strengthened my desire to someday join full-time.

Thanks to Caitlin for her advice and support, Eva and Javier and Pablo for getting me settled in so quickly, Manuel and Fred and Rob from the Web Platform team, and Yoav and Emilio for their help on the Chromium and Firefox parts of my work.

-

Windows is the other major platform that does this. Check out The Old New Thing by Raymond Chen to learn more. ↩

-

Searchfox more or less supersedes MXR and DXR. ↩

-

Igalia has a Searchfox-based WebKit code browser, and I found it useful, but it’s not yet ready for public consumption. ↩

-

See also wpt.fyi, which tracks results of each test case across major browsers. ↩